This piece was broadcast on Sunday Miscellany on 8 February, 2015. If you would like to listen to the podcast, go to the RTE site: http://www.rte.ie/radio1/sunday-miscellany/

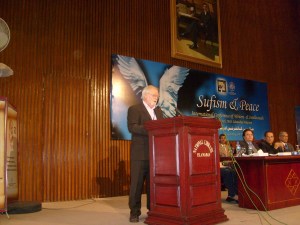

At the centre of the top table is Salman Taseer who was assassinated a few months later by his own bodyguard – he took umbrage at Taseer’s criticism of the country’s blasphemy laws. On his way to court he was showered with rose petals by approving supporters.

I was close to Osama bin Laden when he was still alive. Of course I didn’t realise that as the bus conveying us from our well fortified hotel to the National Library of Pakistan meandered through the endless series of concrete roadblocks that punctuated the main thoroughfares of Islamabad. The steel helmets of soldiers peeping out from sand-bag bunkers, and the armoured cars before and after the bus, were further evidence that the country was in the grip of what we in Ireland might have described as an Emergency.

This was March 2010, and Bin Laden was living in the suburbs of the city with his family and friends around him. I was in Islamabad to participate in a Conference on the topic of ‘Sufism and Peace’. The motley collection of international writers and scholars included many who were deeply versed in Sufism. I myself was no more than somewhat informed on the subject. I had visited the shrines of Sufi saints in India. I had spent some time in a Dervish monastery in Turkey. And of course I had read some work of the Persian poet, Rumi.

It was a curious conference to be organised in Islamabad, with the full support of the existing Government, at a time when fundamentalists, particularly the Taliban, were perpetrating vicious attacks on Sufi shrines. The image in the West was that Pakistani officialdom was sympathetic to Muslim fundamentalists, and was conniving to assist them at every turn. But Sufism was anathema to the fundamentalists; they regarded it as a heresy that had no right to exist inside or outside Islam.

Sufism, like Islam itself, is a vast and varied religious tradition. In a nutshell it can be defined as the mystical brand of Islam. But nutshells and definitions are of little help in understanding something so complex. The central belief of the Sufis is that the experience of God is personal – and achievable, even in this life, by meditation and ascetic practice. They saw religious ecstasy as close to the aesthetic experience, so music, dance, poetry, could all be pathways to the experience of the divine. The practice and propagation of Sufism is based on the relationship of teacher and acolyte. Many of these teachers have been venerated as holy men, just as saints have in the Christian tradition.

Not surprising therefore that artists found much that was congenial in Sufism. Not surprising either that it raised the hackles of the Taliban who had carried out atrocities against Sufi worshippers at sites around Pakistan over the previous years. To them the veneration of saints was a form of idolatry.

But to judge by the absolute and unequivocal support of the government, Sufism had a very strong following in Pakistan. Presiding at each session of the Conference was a member of the Government, including the Minister for Education, and President Zardari himself, whose wife, Benazir Bhutto, had been assassinated four years earlier. The session at which I spoke was presided over by Salman Taseer, Governor of Punjab, who was gunned down by his own bodyguard a few months later because he criticised the country’s Blasphemy Laws.

Most of the delegates were from within Pakistan, and of course all of the audience. It was fascinating to talk with them and to get even a small glimpse into their lives. If I had closed my eyes, I might have been listening to the aspirations of the people of Ireland in the 70’s and 80’s. All they wanted was a peaceful world in which to rear their children and grandchildren. But they saw that world being torn from them by the militarists and the religious hard-liners. They talked of the manoeuvring of these self-appointed arbiters of theological correctness to control the minds of the ordinary people of Pakistan.

So, if I was not an expert in Sufism, what did I contribute to the Conference? I chose to talk about Peace. I started by reciting Yeats’s ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’. This little poem embodied a concept of Peace for many generations throughout the literary and literate world. A sentimental concept. Peace implied withdrawal from life with its tensions and its responsibilities. I described the landscape of the Northwest, where the poem was set, the perfect place to escape to, to escape in. Then I brought them to two small rural towns not more than an hour’s drive from the said Lake Isle. Enniskillen and Omagh. I described what happened there. And they knew exactly what I meant. They had been there, except the names were different, Peshawar, Rawalpindi. And I put it to them that Peace could never be established by withdrawal from the world. And if peace was viewed merely as the absence of violence, or as an intermission between wars, there was no hope. Only a philosophy of engagement with the world had any chance, a philosophy that had to be more powerful than any creed that had heretofore sent people out to kill one another. That philosophy could not be based in any one religion. It had to transcend all religions. Or else it had to operate on a level that joined all human beings at the most basic level, beneath that benchmark line, where humanity unites us, but religion or race has not yet defined nor divided us.

Word count 882